Starting with a tiny radio station launched by Stanley E. Hubbard nearly a century ago, the Hubbard family went on to build a powerful group of television and radio stations nationwide. Here’s how they did it.

Stanley E. Hubbard loved radio. The young entrepreneur spent countless hours tinkering with radio equipment in the early 1920s, and he believed the relatively new medium had enormous promise. But at that time in the Twin Cities, opera singers belting out tunes to piano accompaniment was just about the only entertainment on the local station, owned by Washburn Crosby Company. To Hubbard’s ears, it was dreadful.

Hubbard—then 26—had no money and no media connections, but he did have an idea. He headed over to the popular Marigold Ballroom in Minneapolis and proposed a deal: if they let him have a little studio in the building, he would build a transmitter and broadcast the live music that the ballroom played nearly every night. The owners of the ballroom agreed, and in 1923, the radio station Where All Minneapolis Dances (WAMD) was born.

Hubbard hustled to sell the ads to support his station. “We used to hear about how he had to sleep under the ballroom’s piano and eat donuts,” said his son, Stanley S. Hubbard. The Twin Cities newspapers told advertisers if they spent any money on Hubbard’s radio station, they would have to pay cash in advance to get their ads in the newspapers; they wouldn’t give them any credit. Yet the fledgling station succeeded. His son believes WAMD was the first-ever radio station supported solely from advertising.

The success of WAMD alone was an enormous accomplishment, but for the hard-working, laser-focused Hubbard, the station was not an ending point. It was a launching pad for new ventures and innovations.

As the company expanded to include KSTP-TV, NBC’s first non-owned television affiliate, and KS-95 FM, Hubbard and his wife, Didrikke Stub, and their family remained tied to the Twin Cities community not only through the stations themselves, but through key links to the University of Minnesota and local organizations. That generosity and connection to the community does not come from an interest in self-promotion, but rather a philosophy about the right way to run a business. “My dad put it this way,” said Stanley S. Hubbard, “if you serve the public, the profits will take care of themselves.”

The history of the Hubbards and their company is one of great ambition, calculated risks and a commitment to the communities it serves.

Radio to Television

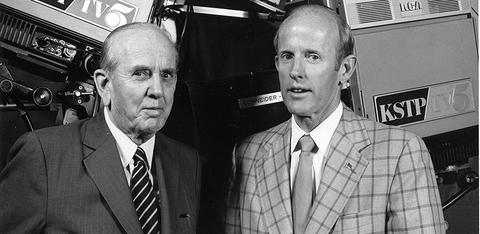

Stanley S. Hubbard loves a good story. Sitting in the modest conference room in his office at KSTP, the 81-year-old CEO peppers the answers of interview questions about Hubbard Broadcasting’s creation and growth with accounts of daring investigative reporting and against-all-odds gambits. “Here’s a pretty good story,” he’ll say with authentic Minnesota understatement as he launches into another tale. “Our news philosophy has always been to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, whether we like that truth or not,” he said.

But first things first. In 1928, the elder Hubbard merged WAMD with a St. Paul station, KFOY, to create KSTP. The station grew to become a 50,000-watt powerhouse; Hubbard eventually bought out the other partners to own the station outright.

At KSTP, Hubbard began to pursue one of his major passions: news reporting. Hubbard loved going out into the field to gather the information, which was written up by his staff. “There’s a phrase called ‘rip and read,’” said the younger Hubbard. “A lot of stations would just take the news from the UP (now United Press International), and later, the AP printout, rip it off and read it as it was.” The elder Hubbard wanted the news be relevant to the Twin Cities, to cover how the national news affected local listeners. When Hubbard started his radio news, there was no radio wire service. So, he and WWJ in Detroit and KFI in Los Angeles leased a wire, at night, which ran from the east to the west coast, and started their own wire news service. That decision convinced UP to provide wire news service to radio stations.

As the station began to flourish, Hubbard continued to look ahead to the ways that emerging technology would allow him to expand his vision of serving the community with news and entertainment. Early on, Hubbard became a great believer in television, and in 1939, he purchased the first TV camera ever sold from RCA, which Hubbard bought on the spot despite jeers that it was an expensive waste. “People said that TV would never work because you wouldn’t be able to get programming,” said the younger Hubbard. “[Warner Bros.’ co-founder] Jack Warner said it wouldn’t work, because it wasn’t possible to produce a new movie for every night of the week. He could only visualize that medium for movies.”

World War II stymied Hubbard’s plans to pursue an entrance into television broadcasting, but in 1948 he launched an ambitious television station. “We were the world’s first full-color TV station, and the world’s first TV station that had regularly scheduled daily newscasts, right from the start,” his son said.

Academic Inspiration

Stanley S. Hubbard, meanwhile, was growing up and learning the business from the inside. Stanley and his brother Richard—who died in an automobile accident in 1972—tagged along with their father while he worked on investigative reports and traveled to broadcasting conventions. (Their older sister Alice was married and raising a family.)

In high school, the young Hubbard worked in the newsroom as a photographer. He spent his evenings driving around with a police radio in his car, heading to the scenes of accidents and crimes, snapping images and developing them for broadcast.

Hubbard and his sons often did the reporting legwork together. The young Hubbard recalls heading to a Northwest Orient Airlines crash site with his father and brother in the early 1950s to investigate a series of fatal crashes involving Martin 2-0-2s. The elder Hubbard persuaded a mechanic working for the airline to take photos of the planes’ cracking wing spars, which were critical structural problems and evidence that suggested they were unsafe to fly. Hubbard says the story helped lead to safer planes. “It’s a pretty good story,” he said. “I saw the place a business can play in the life of a community, trying to right wrongs.”

The young Hubbard could have easily continued on this trajectory with his father, but he also had a dream of playing college-level hockey. Hubbard enrolled at the University of Minnesota and poured his heart into the sport. He readily admits that his drive outstripped his talent, but for coach John Mariucci, Hubbard’s tireless efforts were enough. “Mariucci said to me once, ‘Hubbard, as long as you’re the hardest-working guy here, I’ll always have a place for you,’” he said.

Hubbard loved college hockey, but college academics were another matter entirely. In the midst of one particularly challenging semester, the dean of the College of Science, Literature and the Arts (now CLA) recommended that Hubbard consider trade school instead of trying to succeed at four-year college.

That offhand remark was all the motivation Hubbard needed. “It got to me,” he said. “I went to night school, and I actually opened my books and studied. I got straight As, got back into the U and graduated just one quarter late,” he said, which earned him a degree in sociology in 1955. His professors were convinced he had a future in academia, and one urged him to consider getting a master’s degree.

Hubbard was intrigued, but his father was less enthusiastic. “Do you want to be a student, or do you want to be in business?” he asked his son. For the young Hubbard, the choice was obvious. He would follow in his father’s footsteps.

A Grander Vision

With his son at his side, Stanley E. Hubbard pursued growth at a national scale. Though the young Hubbard’s duties started out small (“My first real responsibility was to buy a flagpole,” he said), they quickly escalated. In 1957, Hubbard Broadcasting bought its first television station outside the Twin Cities market, in Albuquerque, New Mexico. “ I had this idea of building an independent television station in Tampa/St. Petersburg,” he said. “I was able to convince the board to approve it and, therefore, built the first successful independent UHF station in a VHF market—WTOG.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, Stanley S. Hubbard proposed that the company buy television stations in Kansas City, Palm Beach and San Diego—stations that Hubbard Broadcasting could have purchased for a (relative) song, but the board balked. Over time, the elder Hubbard began handing off more responsibilities to his son; meanwhile, his son reinvigorated the company with the kind of bold initiatives that had so long been the hallmark of his father. “I don’t believe we ever lost on a story for lack of resources or commitment, and I believe that goes right back to the founder of the company,” said Scott Libin, who was news director at KSTP-TV from 1998 to 2003 and is now a Hubbard Senior Fellow at the School of Journalism & Mass Communication. “Their decisions go beyond what an accountant’s ledger says. When I was news director there, for example, we paid our interns. This was unheard of at the time. That happened because Stanley S. Hubbard felt we should. It’s because somebody who is deeply invested in the community just thinks it’s the right thing to do.”

By the early 1980s, the young Hubbard saw the next big opportunity on the horizon: satellite television. He knew it could help the company move beyond a market-by-market approach to growth because it opened up the entire country at once. In 1981, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) granted Hubbard Broadcasting the first successful permit for direct broadcast satellite. HUBTV—which later became U.S. Satellite Broadcasting (USSB)—was born.

Just like his father decades earlier, the young Hubbard encountered enormous resistance. “Everybody said it wouldn’t work,” he said. “They said we were crazy.” But, also like his father, Stanley S. Hubbard found fuel in his critics’ dismissals. Hubbard explained that successful technology is actually almost never about the technology itself. It is about whether or not it helps others tell better stories, deliver news faster and provide better service. “People watch programming,” he told an interviewer for The Archive of American Television in 2002, “not pictures.”

Despite Hubbard’s convictions, it was a risky move. “We really bet the business,” Hubbard said. “If it hadn’t worked, we would’ve been broke. We did it because we had this vision of a national broadcast service. That’s what it was about.” Hubbard’s wife Karen, who he says has been a constant source of strength and inspiration, and their whole family, grasped the vision and accepted the risk.

As Hubbard Broadcasting worked to get its large-scale satellite broadcasting technology aloft, it invented satellite news gathering. In 1984, the company rolled out CONUS, a small-dish satellite national news gathering service which meant that, in the words of Stan S. Hubbard’s son, Stan E., “a local television could then write its own headlines” instead of relying on the networks’ evening news for stories of national or international significance.

The USSB satellite lifted off on December 17, 1993, just short of one year after the elder Stanley E. Hubbard passed away. In 1999, Hubbard Broadcasting sold its stake in the business to what is now DirecTV. He told Twin Cities Business in 2011 that the sale netted a profit of “a billion, in round numbers.”

Lasting Legacy

In recent years, Hubbard has ceded much of the company’s decision-making power to four of the next generation: Virginia Morris (Chair and CEO of Hubbard Radio Group); Stan E. (Chair and CEO of Hubbard Media Group, which includes ReelzChannel and F&F Productions in Tampa/St. Petersburg, and controlling interest in Ovation TV); Robert (President of Hubbard Television Group); and Kathryn Rominski (Executive Director of Hubbard Broadcasting Foundation). Part of that decision stemmed from the experiences he had with his own father, which was common among successful entrepreneurs as they got older. He wanted their children to be able to run the company with the boldness that has marked Hubbard Broadcasting’s history. (Daughter Julia H. Coyte is raising a family and not currently working for the company.)

That transfer of power from one generation to another means change, especially in an age where television and radio is streamed, packaged into apps and bundled with a year of free shipping from Amazon. But that change also offers opportunities to carry forward the philosophies that made the Hubbards successful in the first place. Those philosophies include understanding the importance of hard work. “Karen and I didn’t want spoiled, rich kids,” said Hubbard, noting that in high school, their children held jobs mowing lawns, working in restaurants and cleaning hotel rooms. It also includes a long-term vision, which prizes big leaps that can transform the company over modest tweaks that turn quarterly profits.

It’s a legacy that has impacted each generation of the Hubbard family. “I know from the stories that my great-grandfather was a man who persevered, who was willing to try new things,” said Rob Rominski, the grandson of Stanley S. Hubbard, who graduated from SJMC and the Carlson School of Management and is now an associate at the law firm of Stinson Leonard Street. “Even when things didn’t work, it wouldn’t keep him down. He’d pick himself up and go on to the next thing. He was willing to be on the cutting edge. My grandfather obviously inherited that trait from him as well.”

The legacy also includes upholding a commitment to the community that has supported the Hubbards’ company for nearly a century. That’s part of the reason the University of Minnesota has figured so prominently into their philanthropy, according to Hubbard. In addition to generous gifts to the University’s medical and astronomy programs, the Hubbard Family Foundation pledged a $10 million gift to SJMC in 2000. It’s in the company’s best interests to support an institution that will educate many of the journalists who will propel Hubbard Broadcasting into the future. “There are other good schools, of course, but the University of Minnesota is the most important educational institution in Minnesota, bar none, in terms of its effect on everyone,” Hubbard said. “They do a tremendous job.”

The family’s philanthropy is felt every day at SJMC. “The Hubbards have given generously to the University, and they have always trusted us to make appropriate and meaningful uses of these resources, whether that’s scholarship support or state-of-the-art technology infrastructure,” said Al Tims, the director of SJMC. “They gave in the spirit of wanting to ensure that the school was successful, and they’ve had faith in the institution to make the right decisions to support that vision.”

No matter what the future holds for Hubbard Broadcasting Inc. as it moves into its second century—technological innovations, strategic growth, or new markets—its pursuits will surely be infused with the visionary ideas that have powered its growth since the beginning.

As Hubbard might say, it will be a pretty good story.

In 2000, The Hubbard Broadcasting Foundation pledged a $10 million gift to the University’s School of Journalism & Mass Communication. "From Big Vision to Concrete Impact," explores how this gift changed the trajectory of the school.

Erin Peterson lives in Minneapolis. She writes for colleges and universities across the country.