HSJMC professor’s book shows how newspapers led the political struggle.

By Sid Bedingfield

In the spring of 1935, John Henry McCray graduated from college in Alabama and returned to Lincolnville, South Carolina, the tiny African American enclave near Charleston where he grew up. Brimming with ambition, McCray told friends that he wanted to launch a newspaper and use it to fight for equal rights in his home state.

At the time, McCray’s youthful optimism seemed dangerously misplaced. Mired in the Depression and demoralized by 40 years of violent Jim Crow rule, black Carolinians struggled each day merely to survive. As one observer noted, they seemed trapped in a morass of economic exploitation and political hopelessness. e organizations that dominated black civic life in the state—churches, schools and NAACP chapters—had grown either defeatist or moribund. White leaders believed the issue of white supremacy had been settled in the South, and some of the most prominent voices in the black community appeared to agree.

Over the following decade, however, African Americans emerged as a political force in South Carolina. NAACP membership increased from fewer than 800 in the mid-1930s to more than 14,000 a decade later. And the new movement won a string of victories. In the 1940s, black South Carolinians overturned the state’s system of unequal pay for black teachers, won the right to participate in Democratic Party primaries, influenced the outcome of a U.S. Senate election and led a school desegregation suit that would lead to Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court case outlawing segregation in public schools. These successes served as a turning point in the political history of the state and the nation. As one historian put it, the NAACP activists who led the fight in South Carolina in the 1940s served as the “vanguard” of the massive civil rights struggle that would emerge across the South the following decade.

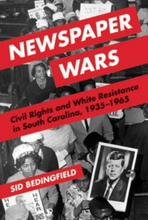

The surge in activism that began in the late 1930s and accelerated through the 1940s raises an obvious question: How did a movement planted in such desolate terrain manage to take root and grow so quickly? In my book, Newspaper Wars: Civil Rights and White Resistance in South Carolina, 1935-1965, I try to answer that question.

The Role of Journalism

Demographic and social changes that swept the nation during the 1930s and ’40s created two of the three conditions that social movement theorists believe are necessary for successful collective action. The Great Migration of African Americans leaving the South during the 1930s created political opportunities by increasing black voting clout in the North, particularly in the large industrial states where national elections were decided. In the South, urbanization helped produce new mobilizing structures in cities and small towns, making it much easier for black churches and the NAACP to unite the community and build support for protest.

Yet these developments alone did not ensure the rise of a robust civil rights movement. To achieve that, black communities in the South needed leaders who could infuse these social and demographic changes with political meaning. They required powerful new voices who could carry out what sociologist Douglas McAdam calls “the collective processes of interpretation ... and social construction that mediate between opportunity and action.”

My book argues that the civil rights struggle was more than a litany of court cases and voter registration drives. At its core, it was a cultural contest. In South Carolina, black activists and white segregationists crafted narratives that competed to interpret the meaning of the African American fight for political and social equality. They used the tools of mass communication and political symbolism to try to de ne citizenship and establish the proper boundaries of civic life. Both were pursuing a distinctly political goal: to mobilize supporters, persuade potential allies and shape public opinion on the critical question of race and citizenship.

The black and white press operated at the heart of this meaning-making process. In the African American community, where a strategy of cautious accommodation of white supremacist rule remained prevalent, a radical newspaper emerged in the late 1930s to promote a new conception of what citizenship required. McCray’s Lighthouse and Informer served as the public voice of a political reform movement that included an aggressive NAACP and a rising Democratic Party insurgency. Using the newspaper as a means of command and control, the movement mobilized black community support and launched a coordinated assault on the barriers white society had erected to block black participation in the state’s civic life.

The White Backlash

Faced with this new challenge, white newspaper editors, often in collusion with political o ce holders, struggled to redefine the meaning of white democracy. They would continue to pursue what an earlier historian had called the “central theme of southern history”—the region’s e ort to remain a “white man’s country.” Yet the nation had changed since their forebears had fought to restore white supremacy at the turn of the twentieth century. With northern public opinion turning in the years after World War II, white editors in the state worked to create a new defense of white rule in the South that would restore its legal and intellectual credibility within the nation’s larger democratic narrative.

By moving the state’s newspapers from the periphery to the center of the political action, my book encourages readers to reconsider the role journalism played in the fight over civil rights. John McCray and his primary allies at the Lighthouse and Informer—Modjeska Monteith Simkins and Osceola E. McKaine—are significant historical figures who deserve more attention in the study of the nation’s black press. At a time when most black newspapers in the Deep South were assumed to be cautious and conservative—much like the Scott family’s Atlanta Daily World—the Light- house and Informer called for direct confrontation with white supremacy. In the 1940s, McCray and his allies challenged their readers to “rebel and fight” for their rights as American citizens, to reject the “slavery of thought and action” that created “uncle Toms and aunt Jemimas” and become “progressive fighters for the emancipation of the race.”

This study also focuses on white journalists and their role in shaping the response to the movement McCray’s newspaper helped launch. In South Carolina, journalists at white daily newspapers did more than document and interpret public events; they served as independent and distinct political actors engaged directly in the state’s political process. In the wake of the Brown decision, they editorialized in favor of massive resistance, but they also helped implement that policy through the creation of White Citizens’ Councils and other political organizations. When massive resistance began to fail, the same journalists turned to partisan politics and played central roles in creating a new political home for white segregationists in a conservative Republican Party in the South.

In the 1960s, white southern journalists began experimenting with new narratives designed to build the GOP and undermine growing black political activism in the South. My book shows how South Carolina journalists joined forces with William F. Buckley Jr. and his political journal, National Review, to begin developing a new rhetoric of so- called “colorblind conservatism” that could attract southern segregationists to the rising conservative movement without alienating northern supporters.

Though geographically small, South Carolina has always played an outsized role in the racial history of the nation. In many ways it has served as ground zero for the most contentious and vexing issue of American democracy. From the debate over slavery at the constitutional convention through the first shots at Fort Sumter and the rise and fall of Jim Crow, the Palmetto State has taken the lead in the battle to stand still. No state has tried harder to rebel against the arrival of the modern world. And in each confrontation, South Carolina newspapers played significant roles. From the secessionist re-eaters at the Charleston Mercury to John McCray’s fight for black voting rights and the white press’ embrace of Goldwater Republican- ism, the history of journalism has been inseparable from the state’s politics. I argue that South Carolina provides a rich and fascinating landscape for the study of journal- ism and its role during times of political change.

Sid Bedingfield is an assistant professor in the Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Minnesota. His book, Newspaper Wars: Civil Rights and White Resistance in South Carolina, 1935-1965, was published in Fall 2017 by the University of Illinois Press. Bedingfield, a former newspaper and television journalist, received his doctorate from the University of South Carolina in 2014.